Intuitive design, seamless, frictionless, streaming, on-demand service, one-click ordering, mobile access, optimization and efficiency — these are some of the great promises of the digital age and, for many of us, they have re-defined the ways we shop, consume entertainment, find a bed to sleep-in or organize our transportation. As utopian as this sounds, we know that this promise does not exist equally for us all and that creditcards, bank accounts, limitless data plans, high-density and high-fashion zip codes, and discretionary budgets are not universal entitlements, even if app developers sometimes operate as though they are. As William Gibson said, “the future is already here, it’s just not evenly distributed.”

Less acknowledged are the ways in which user-friendly and intuitive design shields us from some of the operational complexities that make this seemingly simple elegance function, streamlining processes and concealing endless lines of computer code. But what if this drive for efficiency, seamlessness and invisibility has inadvertently done something more insidious too? What if, when we look behind the curtain, we see the ways this drive for efficiencies has supported our agency but maligned our relationships? Accentuated our egos at the expense of our social consideration? Atomized and divided us instead of pushing us to see the common experiences that unite us? And what if it has been aided in accomplishing all of this through that which it fails to show us?

Our mobile devices have also played their role in refracting our visions of the world through the prism of the self. Yes, they allow us to connect with people, ideas and images in distant places and across time, but they also constrain our perception of the physical and social worlds through which we move. These intimate devices, that live in our hands and pockets, can create the illusion of magical and instantaneous gratification of a world that waits to satisfy our personal needs and desires. And yet, there are still real-world realities that must be activated to make this magic happen. Uber drivers have traffic to navigate, families to support and bills to pay; filmmakers need to write, cast and film the content they create for streaming services; and somebody has to wash sheets and clean bathrooms before the next Airbnb guest arrives. It is the role that seamlessness plays in making this complexity disappear, (i.e. the system) that demands our attention.

The inspiration for this musing came from recent in-depth ethnographic thinking about shared vehicle ownership for Renault-Nissan-Mitsubishi Alliance’s innovation group, Future Lab.

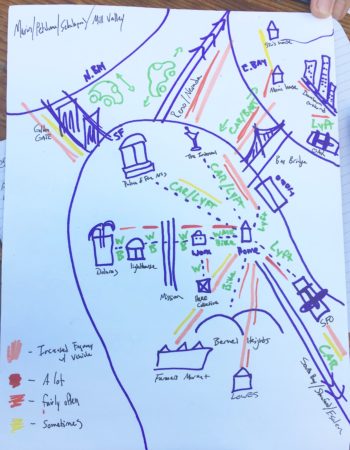

During this six-month long study, participating households shared both life calendars and vehicles. Over time, we came to see many ways in which participants experienced the shared vehicle differently from the many other modes of transportation and emerging services that were available to them in the city where they lived.  Many came to view mobility as a complex ecosystem and actively continued to use combinations of these alternate modes of transit even when they had access to their shared vehicles. In the process, their evolving thoughts on ownership, inter-personal relationships and the material culture of mobility all influenced how they viewed these alternate modes. It helped explain why train cars were seen as dirty, neglected and dangerous; why dog hair found in a ZipCar was viewed as unacceptable but only an issue in need of resolution in the shared vehicle; and it showed the ways in which calling up a Lyft at the airport caused one to contemplate personal culpability for traffic congestion in a new way. Most impressive was seeing the ways our participants were able to ladder up their lived experiences of accountability and consideration from within their sharing groups, to systemic implications. Our long ethnographic engagement allowed anthropologists and participants to reflect together on the particular importance that making these interdependencies visible played in supporting this heightened consciousness.

Many came to view mobility as a complex ecosystem and actively continued to use combinations of these alternate modes of transit even when they had access to their shared vehicles. In the process, their evolving thoughts on ownership, inter-personal relationships and the material culture of mobility all influenced how they viewed these alternate modes. It helped explain why train cars were seen as dirty, neglected and dangerous; why dog hair found in a ZipCar was viewed as unacceptable but only an issue in need of resolution in the shared vehicle; and it showed the ways in which calling up a Lyft at the airport caused one to contemplate personal culpability for traffic congestion in a new way. Most impressive was seeing the ways our participants were able to ladder up their lived experiences of accountability and consideration from within their sharing groups, to systemic implications. Our long ethnographic engagement allowed anthropologists and participants to reflect together on the particular importance that making these interdependencies visible played in supporting this heightened consciousness.

Just as our cohort reflected on ripple impacts and came to see mobility as an interconnected problem that implicated us all, so too have there been other recent signs of cracks in the facade of the digital promise.  Significantly, these signs of discontent have come both about and within tech: from citizen protests against ubiquitous and irksome sidewalk scooters that were used to barricade the polarizing private tech shuttles in San Francisco, to the new whispers of worker and women’s solidarity within tech, such as the recent Google walkout. Not only have these protests shown that digital promise is not perhaps as frictionless as advertised, but also that we are all implicated in these visions of utopic futures, the least among us as much as those most privileged. In the spirit of making sense of this growing collective consciousness, it is worth considering the role that elevating individual needs and privileges has played in concealing the links that bind us to one another and to our environment and how that has exacerbated some of these divisions in the process.

Significantly, these signs of discontent have come both about and within tech: from citizen protests against ubiquitous and irksome sidewalk scooters that were used to barricade the polarizing private tech shuttles in San Francisco, to the new whispers of worker and women’s solidarity within tech, such as the recent Google walkout. Not only have these protests shown that digital promise is not perhaps as frictionless as advertised, but also that we are all implicated in these visions of utopic futures, the least among us as much as those most privileged. In the spirit of making sense of this growing collective consciousness, it is worth considering the role that elevating individual needs and privileges has played in concealing the links that bind us to one another and to our environment and how that has exacerbated some of these divisions in the process.

In the re-launch of the New Twilight Zone there was an episode in 1985 called a Matter of Minutes, based on a short story by Theodore Sturgeon (the inspiration for Kurt Vonnegut’s fictitious writer Kilgore Trout, for those of you who really want to go deep). The story’s concept is that time is actually a physical place that is being constantly built by a faceless set of stage-hand/workers who are invisibly constructing this reality for us, one minute at a time. It is to this story and these images that I keep returning, when I think about this idea of the invisible system, how it is animated and how easy it is to move though this space unaware of this effort or our own privilege. The effect of this fantasy is as chilling as it is provocative but it begs a question of what you would do differently if you became aware of this invisible system.

What might it look like to design technologies that reveal systems (designing for social context as the anthropologist might say) and our interconnected place within them, even as they continue to also make aspects of our lives more convenient? Certainly there is risk of social unrest in a more informed citizenry, but doesn’t the dilemma of reconciling knowledge and free will speak to a fundamental value of human research at the least, and the human experience at most? Perhaps with greater transparency of the system we can aspire to a more evenly distributed future in the present?

Leave a Reply