As tourists we set out to create relationships with places. This at least is one of the most enduring and certainly romantic ideals of travel. The wandering expatriate who finds a soul-affirming connection to a foreign city or culture, the occasional vagabond who discovers something about her humanity angling in a high country trout stream, the naïf turned impassioned connoisseur who has stumbled on a region’s food, drink, art, music…life. Look through any flight magazine, or lifestyle publication, countless blogs, Instagram feeds and Pinterest boards, a good hunk of the Sunday NY Times. There are endless variations on this theme. They tell us something essential, yet historically specific, about our “modern” hearts and yearnings. They also tell us something essential about the nature of places.

As tourists we set out to create relationships with places. This at least is one of the most enduring and certainly romantic ideals of travel. The wandering expatriate who finds a soul-affirming connection to a foreign city or culture, the occasional vagabond who discovers something about her humanity angling in a high country trout stream, the naïf turned impassioned connoisseur who has stumbled on a region’s food, drink, art, music…life. Look through any flight magazine, or lifestyle publication, countless blogs, Instagram feeds and Pinterest boards, a good hunk of the Sunday NY Times. There are endless variations on this theme. They tell us something essential, yet historically specific, about our “modern” hearts and yearnings. They also tell us something essential about the nature of places.

Places are complicated and often fragile things, a tangled arrangement of the imagined and the concrete. The pizza place displaced by gentrification, where dollar slices were once emblematic of the old neighborhood. The Champs-Élysées, for decades the pinnacle of luxe, now peppered with stores for mass market American brands. The Dome at Yosemite, a symbol of the wild untrammeled West, that is visited by millions every year. Places such as these, and countless others, populate a realm that’s almost, not quite, autonomous from space. Places are dreamed and remembered. We read and write places. We take places with us. We come back to them with fresh (changed) eyes. This makes places quite different from “sites” which have specific geographic vectors. Sites are mappable things. We can find them on our GPS. Places have a fluid focus. As Edward Casey, the eminent philosopher of place observes, the “in” is in communication with the “out.”

Places are complicated and often fragile things, a tangled arrangement of the imagined and the concrete. The pizza place displaced by gentrification, where dollar slices were once emblematic of the old neighborhood. The Champs-Élysées, for decades the pinnacle of luxe, now peppered with stores for mass market American brands. The Dome at Yosemite, a symbol of the wild untrammeled West, that is visited by millions every year. Places such as these, and countless others, populate a realm that’s almost, not quite, autonomous from space. Places are dreamed and remembered. We read and write places. We take places with us. We come back to them with fresh (changed) eyes. This makes places quite different from “sites” which have specific geographic vectors. Sites are mappable things. We can find them on our GPS. Places have a fluid focus. As Edward Casey, the eminent philosopher of place observes, the “in” is in communication with the “out.”

That said, places are embodied in a primary sense. We have physical connections to place—its smells, tastes, sounds, light, colors; its topography, terrain, geology, geography; its people, its built-ness, its architecture, its artifacts. Time also imposes physical and lived relationships to place — its tempos and rhythms, its music, its noise, its changes, its days and nights, its seasons, its history. You could say what makes a place a place is its containing-ness, its character of holding these things, the concrete, imaginary, and experienced, “in place.”

Tourists are seeking connections that hinge on these very qualities of place. They want a part, even a bit part, in the creative activity of place-making, this ongoing conversation between visitor and locale. Such experiences speak to a specific kind of tourism. Call it the romantic, ethnographic mode. It is about discovery, connecting the dots, participating in the storied nature of place, authorship. Above all it is a place bound experience of immersion. And a delight, at least one hopes, in a particular sort of touristic context — a sentient body in place that is simultaneously on a journey into place. This filling-in of place (which is both ethnographic and romantic) with our own place-bound imaginings and experiences triggers transformations, some big some small, in ourselves as well as the places we visit.

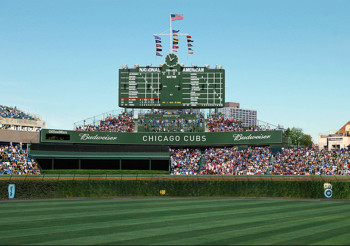

Social media has an uncanny capacity for filling in place. There is a kind of authorship at work here certainly. Tweets, FB, Tumblr, Instagram, Vimeo posts, etc. draw places into digital space where they are shared, “liked”, reposted, and charged with social meaning. This could be quite ephemeral and trivial. But sometimes, as we pursue, or try to capture the spirit that animates place, place becomes the heart of the conversation. E.g. Instagram post of Sally with beer and hot dog at Wrigley Field, # baseball nirvana. Here the embodied: Sally, beer, hotdog, comingle with the social imaginary: # baseball nirvana, to fill an iconic place, Wrigley Field. And how do they “fill” Wrigley Field? By participating in, you could say communing with its local spirit…no?

Social media has an uncanny capacity for filling in place. There is a kind of authorship at work here certainly. Tweets, FB, Tumblr, Instagram, Vimeo posts, etc. draw places into digital space where they are shared, “liked”, reposted, and charged with social meaning. This could be quite ephemeral and trivial. But sometimes, as we pursue, or try to capture the spirit that animates place, place becomes the heart of the conversation. E.g. Instagram post of Sally with beer and hot dog at Wrigley Field, # baseball nirvana. Here the embodied: Sally, beer, hotdog, comingle with the social imaginary: # baseball nirvana, to fill an iconic place, Wrigley Field. And how do they “fill” Wrigley Field? By participating in, you could say communing with its local spirit…no?

Well maybe and then again maybe not. Social media also has the uncanny capacity to decontextualize place. The simultaneity of social media, its capacity to locate us both here and there can actually take us out of place, or at the very least break the charm of immersion and participation in place that we have been describing. It is quite possible that interweaving the digital with the concrete can enrich and enliven place, drawing digitally dispersed others, along with an endless stream of links to other “sites” into our place-bound moment but it can also have a destabilizing effect. Is Sally communing with legendary Wrigley field when she is posting to her friends and followers on Facebook and Instagram? Or is she doing something else? Creating an online voice, a persona or simply being “on” Facebook and Instagram rather than at Wrigley? Perhaps a bit of both.

In what seems a radical reversal of our touristic desire to build relationships to places, selfie mania, call it the narcissism gone viral mode of travel, has tourist destinations as well as cultural observers on high alert. The romance with place (driving so much tourism) is shattered when place is simply a platform to broadcast images of the self, especially those salacious or crazy shots staged to go viral on platforms such as Instagram and YouTube. Somehow this seems different from the “I was there” impulse where places provide some relevant context. E.g., here’s Sally again standing on the Great Wall of China waving to the camera # hi from China. Instead the touristic moment, and you could say its focal location, has migrated on to social media, to YouTube, Instagram, etc., driven by the overweening desire to go viral. E.g., here’s Sally urinating on the Great Wall of China! # hi from China.

Such travel frolics seem destructively nihilistic (or at least tasteless), but apparently are not infrequent and not beyond the pale, if one is to count followers or “likes” on social media according to recent reports. With some historical distance perhaps such behavior can be folded in to a hallowed tradition of sophomoric, mindless, buffoonery. But once our relationships to places become so attenuated, (the romance shattered) and the things that places hold for us, touch, tastes, sounds, colors, shapes, legends, people, history, are displaced by another field of engagement where the viral selfie presides, place itself will be tragically vulnerable.